It was an average Tuesday night. Returning home from the grocery store after work, just past 6:30 pm, like always, Elizabeth tossed her keys in the dish on the small table in the entryway and placed her grocery bag on the floor beside it. She flipped the lights on, shrugged off her coat, and hung it on the hooks next to the front door. She muttered to herself, bits and pieces of thoughts, about hoping the chicken was defrosted or else she’d need to find something else to cook, and about how she’d really like to change the rug in the entryway hall, and about how she needs to remember to bring that notebook for Sheryl tomorrow.

As she walked down the hall toward her living room, the floor began to shake. Growing up in California, she knew what an earthquake felt like, and this was somehow different. It felt as if the floorboards themselves were shaking rather than the building or the earth.

She reached out to stabilize herself, knocking a photo of her father off the wall in the process. Rather than feeling the textured paint of the hallway wall under her palm, it was as if she felt it in points and spots around her hand, and a cold, dark nothing elsewhere. But there was more. She could feel the wood beam beneath the drywall, the metal nails, the rubber-coated wires. Her hand felt as if it were both on and in the wall simultaneously, while also being somewhere else entirely.

She looked down at her feet and could see her socks, her bare feet, the wood floors, the ground beneath her house, everything in fast moving bits and pieces, shifting back and forth, overlapping out of order and merging into nonsense patterns. She put her hand in front of her face and here and there on her palm, she could see all the way down the hall and out past her living room windows, down the street, and beyond.

It all became too much, and her head went cold as she passed out, not even feeling the floor come up to meet her.

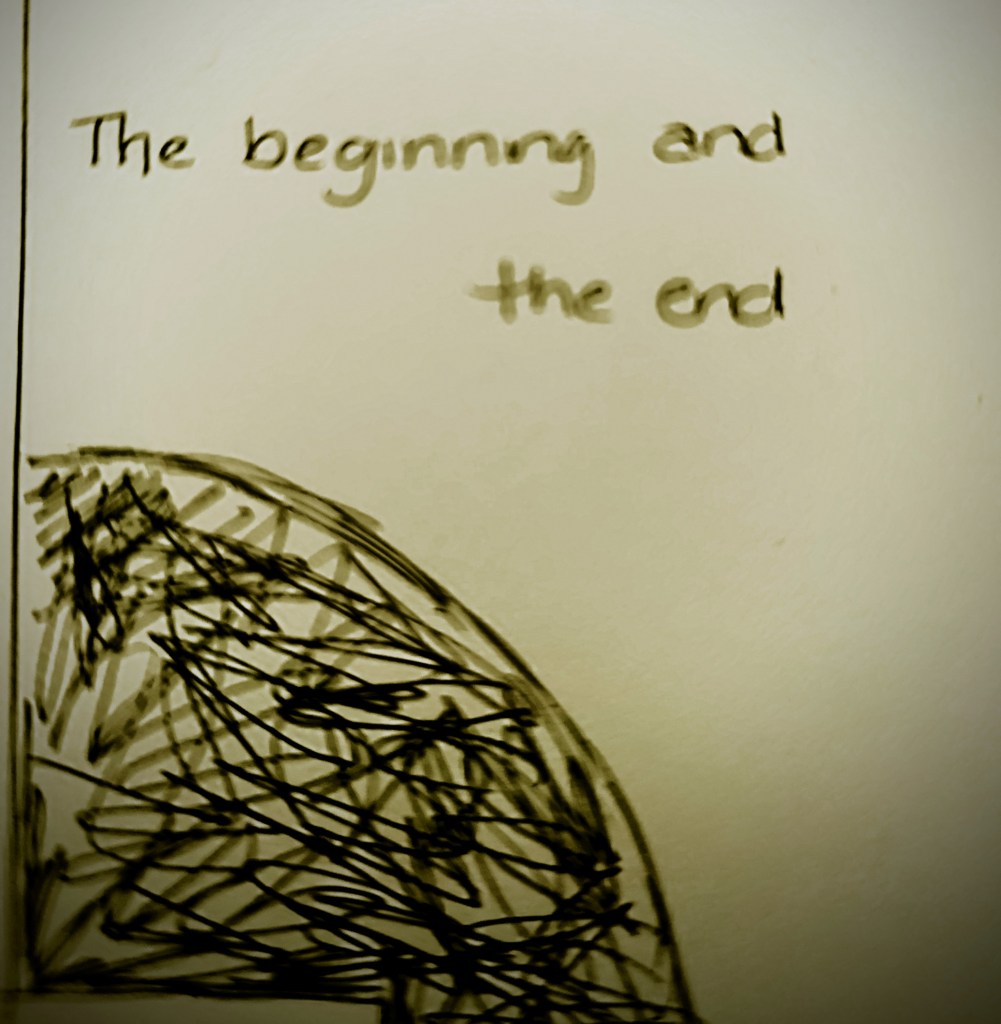

Time is a series of rings circling a central point

that is the beginning and the end.

Some rings are long and thin,

while others are rough and wide.

The first shift is the hardest.

Elizabeth awoke in a small, dark room on a twin-sized bed. She checked the clock. An hour to go before work. She rolled over and pulled the covers up over her shoulder, stretching her legs out to the foot of her bed and letting out a soft yawn.

Another Thursday, she thought, sitting up and rubbing her eyes.

After showering and a quick breakfast of toast with honey and butter, she walked to catch the bus to work. It was a fall day in Dallas, but the sun still blazed on her arms through the bus window, making her sweat under her coat sleeves.

Her workday passed much as it always did, filing paperwork, answering phones, taking messages. Everyone in the office was buzzing about the big event the next morning, the other girls chattering about what dress they might wear, and what they thought others would be wearing, and who was taking whom to watch. Elizabeth, feeling her typical level of invisibility in the office, ate her lunch in the park outside, watching the cars rush up and down the street, seeing people milling in and out of the county court.

Suddenly, it was growing dark outside. Elizabeth had been caught up in a particularly frustrating task of locating a specific box of books for a client on the sixth floor. Because of the renovations, everything was a mess, and while she could have sent one of the salesmen to locate it, she found she liked the quiet solitude of the upper floors, away from the chatting and laughs.

Deciding she’d locate the box on Monday, Elizabeth headed downstairs to her desk, grabbed her things, and walked to the door. When she got outside, the chill of a crisp late November breeze reminded her of her coat. A janitor in the lobby walked her up to the sixth floor, unlocked the door, and turned the lights on so she could find it. He left, asking her to close up on her way out. She found her coat under a few boxes near the East wall, flipped off the lights, and headed home.

As she walked through her front door, she felt the floors shaking in a peculiar way.

I’ve felt this before, she thought, though she wasn’t sure where or how or when. She put her hand out to the wall to steady herself, and felt her hand go through the wall, as her feet felt the bare wood under the tiles of her entryway. She heard the faint click of her front door closing as the world went dark, and she hit the floor.

Some rings spin quickly

around the central point,

rocking and wobbling.

Others move

slowly

and

steadily.

You get used to the shift.

Elizabeth found herself staring up at a rough wood ceiling, a cabin roof, lying on a mattress filled with straw. The rooster outside cawed and screeched, and the hens could be heard bobbling about the yard, pecking at the hay and seeds and pebbles.

She hurriedly got up and began pulling on her stockings and apron. The cabin was cold, and the embers in the fireplace smoked lightly and lazily. Across the one-room house, her housemate slept soundly in her bed, snoring softly, her chest rising and falling with a steady rhythm. Elizabeth’s housemate worked in the tax office in town, helping the British soldiers record tax intakes and organize their correspondence. Being Saturday, she could sleep in and spend her day walking the square or watching the boats in the harbor, but Elizabeth wasn’t so lucky. The bakery could not afford to stop for a day. After all, everyone needs bread, regardless of what day of the week it is.

The streets of Boston felt tense, with British soldiers milling about every corner and potential rebels glaring at them across mugs of beer or the daily newspapers. Elizabeth had no time for politics between her daily work and nightly studies. She was learning to be a healer from an older woman in town who gave her books to read, covering everything from animal butchery to herbal medicine.

Her mind wandered as she rushed down the busy roads toward the bakery, trying to recall which plant was best for headaches and which for nausea. She turned a corner and accidentally bumped into a British soldier standing with a cup of coffee in one hand and a letter in the other. His coffee spilled across the page, sending the black ink spiraling across the page. Elizabeth hurried onward, not wanting to draw his ire, so when he turned to find the culprit, he found a decidedly drunk rebel leaning against a wall, talking in slurred words to a group of men.

Behind her, Elizabeth could hear the British soldier confronting the man, the man yelling back, and an altercation beginning, the noise drawing a crowd from every neighboring street. Elizabeth pushed on and opened the door to the bakery. As she walked through the entrance, her head began to spin. The floor felt uneven and shaky, and as she raised her hand to her head, she felt her vision blur, the bakery around her going dark.

Every so often,

rings collide:

an inflection point,

where their journey around the central point may restart.

It’s at these points

where you shift

from one ring to another

to journey through

to the next inflection point,

when you’ll shift again.

Elizabeth could feel the weightlessness and cold, empty dark before she opened her eyes. Even when she opened them, she found nothing, floating in a blank space.

She began to think to herself, “Where am I?” but before the thought finished forming, an echoing, soft voice replied.

This is the beginning

And the end.

The response made no sense to her, but she couldn’t finish forming full sentences before the voice began, sometimes so softly she could hardly hear, only catching a few words here and there, none of which made any sense to her.

Creating moments and cycles.

Begin again.

The inflection points.

You shift.

The word shift struck something in her, and she felt memories flooding over her mind. An apartment in the late afternoon. An office building with boxes of books. A hay-filled mattress and red-coated men. Something felt important about these memories, but she couldn’t place them.

She remembered going into the room with the boxes of books, finding her coat, and leaving.

But, you didn’t lock the door.

The voice whispered, its tone somehow accusatory. Her conversation with the security guard slowly came into focus. He had asked her to lock it, and she couldn’t remember locking it on the way out.

The door was unlocked,

so he got in.

He had a view.

He aimed,

shot, and ran.

An image of the British soldier flashed before her, and the sounds of the fight she caused rang in her ears.

The drunken man died,

and his death sparked a war,

staining blue water brown

and streets with red.

Every so often,

rings collide:

an inflection point,

where their journey around the central point may restart.

It’s at these points

where you shift

from one ring to another

to journey through

to the next inflection point,

when you’ll shift again.

The voice stopped, silence, and Elizabeth felt her skin tremble as her head went blank and consciousness slipped away.